The rise and fall of the Vanderbilt family still pervades American historical lore, from the millions that pilgrimage to glimpse their remaining East Coast mansions to the references in popular culture (i.e. Nate Archibald, in Gossip Girl), always to a class of privilege. The Vanderbilts came from modest beginnings however, in a farmhouse on Staten Island, and rose to prominence with the arrival of the railroad. In an incredible book called Fortunes Children, descendant Arthur T. Vanderbilt II, he writes that

“the bits and pieces of history that chronicle the four-generation saga of the Vanderbilt Family are scattered everywhere like a broken string of pearls…But nowhere is that curious combination of magnificence and absurdity that was the Gilded age more palpable than in the great country homes that still stand today as monuments to their dreams and fantasies.”

Here at Untapped we’ve decided to uncover the remnants of what is left of the Vanderbilt architectural legacy in New York City. Within 70 years of patriarch Commodore Vanderbilt’s death, the last of the 10 gilded family mansions on Fifth Avenue had been demolished. But not all has been lost, if you look closely enough.

Photo from Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection

Photo from Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection

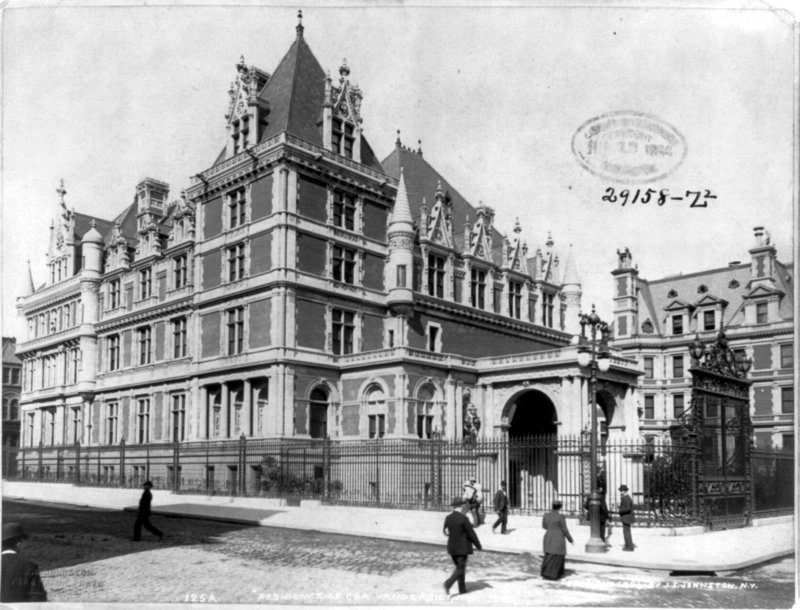

Cornelius Vanderbilt II’s 1882 (1893 renovated) mansion exemplifies both the ambitions and extravagance of the nation’s prosperous. When Commodore Vanderbilt died in 1877, he left Cornelius II a $5 million inheritance. Cornelius II used this money to purchase and demolish three brownstone houses on the southwest corner of 57th Street and 5th Avenue in preparation for his new mansion. His wife was instrumental in the extravagance–it was “common belief that Alice Vanderbilt set out to draft her sister in law [Alva Vanderbilt]’s Fifth Avenue chateau, and dwarf it she did.” (Fortunes Children). Cornelius’ mansion was reportedly the largest single family house in New York City.

Vanderbilt commissioned George B. Post to design the mansion and John LaFarge, Augustus Saint-Gaudens and his brother Julius, Frederick Kaldenberg, Philip Martiny, Rene de Quelin, and Frederick W. MacMonnies to design its interior. Post created a red brick and limestone chateau, which stood out amongst its brownstone neighbors.

In the 1890s, the Gold Coast mansions became larger and more opulent. As a result, Vanderbilt decided to enlarge his own mansion. He purchased and demolished five more brownstone houses on 58th Street. “I want to dominate the Plaza,” he claimed. George B. Post was reenlisted, along Richard Morris Hunt. Sadly, Vanderbilt was only able to enjoy his renovated mansion for a few years. He died unexpectedly in 1899. By all accounts, the house was built more for show than for comfort, as “visitors found the mansion chilly and uncomfortable, built for social functions, not for living.” It seemed to suit the owner though, and Arthur T. Vanderbilt II reports that “a lifelong acquaintance of Cornelius Vanderbilt [II]’s remarked that he never once recalled seeing him smile. There is no evidence that this story was apocryphal.”

Photo from Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection

Photo from Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection

Alice Vanderbilt remained in the house until 1926 when she sold it to Braisted Realty Corporation for approximately $7 million. The wrecking ball laid waste to Post’s masterpiece. Fortunately, a few relics were salvaged from the Vanderbilt Mansion and can still be seen today.

Vanderbilt’s guests would have entered the mansion’s grounds through a pair of monumental gates. The gates, which are depicted in the above photo, can now be found in Central Park. Thy were designed by George B. Post and were forged in Paris in 1894 by Peregotte & Dauvillier. Miraculously, the gate survived though there does not appear to be any record stating why. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, Cornelius II and Alice’s daughter, donated the gates to Central Park in 1939 where they have remained.

After passing through the monumental gates, visitors would reach the porte cochere. There, they would be greeted by six sculptural reliefs executed by Karl Bitter. They depicted musical groups of seven boys and seven girls singing, and were reminiscent of Italian renaissance works. When the mansion was demolished, two of the friezes were salvaged and installed in the Sherry-Netherland Hotel. They can still be seen in the hotel’s lobby. The remaining four bas reliefs disappeared without a trace.

Upon entering the entrance hall, visitors would have gravitated toward the hall’s fireplace. The reddish brown fireplace was flanked by marble caryatids, designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, representing Pax and Amor (peace and love). The fireplace was surmounted by a LaFarge designed mosaic depicting a classically robed maiden sitting on an excedra with a latin inscription. The inscription was supplied by Cornelius Vanderbilt himself and reads in translation, “The house at its threshold gives evidence of the master’s good will. Welcome to the guest who arrives: Farewell and helpfulness to him who departs.” When the house was renovated in the 1890s the fireplace was transfered to the family sitting room on the second floor. When the mansion was demolished the fireplace, along with a number of paintings, was donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The fireplace is currently on display in the courtyard of the Museum’s American Wing.

Today, the property at 742-748 Fifth Avenue, the original address of the Cornelius Vanderbilt II mansion, is now the department store Bergdorf Goodman. Stay tuned for our continuing series on Gilded Age mansions, then and now.

Next, see more of the Gilded Age Mansions on Fifth Avenue. Additional reporting by Michelle Young.